Some district courts express skepticism over arbitration provisions in consumer online terms of use agreements. In March 2020, one such court denied a motion to compel arbitration, finding that the online terms of use at issue, which contained a mandatory arbitration provision and class action waiver, was presented in a manner too inconspicuous to give the plaintiffs constructive notice that they were agreeing to be bound by the arbitration agreement.1 A Ninth Circuit panel ultimately reversed the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California's decision, with the majority concluding that the website provided sufficient notice of the terms of use to a reasonably prudent user.2 The Ninth Circuit recently denied a request by the plaintiff for en banc review of the decision by the full Ninth Circuit.3 In other words, the defendant prevailed in the long run, and the individual plaintiff's claims will now be decided in arbitration, thereby eliminating the potential for a class action. But it took well over a year and undoubtedly significant legal fees to reach that result. The defendant likely could have avoided litigation over the enforceability of its terms of use by using a different online presentation.

Background

Intuit owns TurboTax, an online tax-preparation service. In 2019, the plaintiffs filed a class action lawsuit against Intuit alleging that Intuit fooled a class of consumers into paying for its tax-preparation services when they were entitled to use its free filing option.

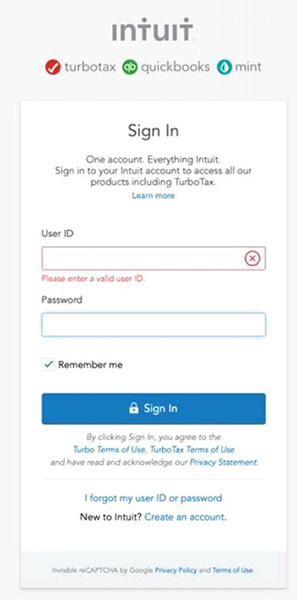

Intuit moved to compel arbitration, arguing that the plaintiffs were bound by the arbitration agreement in the Intuit Terms of Service for TurboTax Online Tax Preparation Services - Tax Year 2018 (the Terms), which Intuit argued plaintiffs agreed to every time they signed in to use Intuit's tax preparation software. The Terms were presented on the applicable sign-in page as follows:

A consumer who clicked on the "TurboTax Terms of Use" hyperlink and read the Terms would have seen a mandatory arbitration provision. This presentation is similar to that used by many internet companies and app providers.

United States District Court for the Northern District of California's Analysis

The main question that the district court grappled with was whether there was a valid agreement to arbitrate. Under California contract law, a valid agreement requires the parties' "mutual manifestation of assent" to be bound by the terms of the contract.4 Further, an offeree cannot be bound by the terms of a contract if the offeree does not know that a proposal has been made.5

Specifically, "sign-in wrap" agreements (similar to those employed by Intuit, where a sign-up screen states that acceptance of a separate agreement is required before the user can access the service) are valid and enforceable when the existence of the terms was reasonably communicated to the user.6 If the plaintiffs "were on inquiry notice of the arbitration provision by virtue of the hyperlink to the Terms on the sign-in page and manifested their assent to the agreement by clicking 'sign-in,'" then there was a valid arbitration agreement.7

The district court held that there was not a valid arbitration agreement because the plaintiffs lacked adequate notice of the Terms. In making this decision, the district court relied on the following facts:

- The hyperlink to the Terms was in a contrasting color but it was not underlined, which fell short of what the district court considered the "gold standard" for assessing whether "the hyperlinked text itself was reasonably conspicuous" and identifiable as a hyperlink.8

- The notice and the applicable hyperlinks were in the lightest font on the entire sign-in screen, which the district court thought made it less likely for a consumer to notice;

- The notice contained multiple, similar hyperlinks (i.e., the "Turbo Terms of Use" and "Turbo Tax Terms of Use"), and only the latter included the arbitration agreement that Intuit was seeking to enforce; and

- Less than 0.55 percent of users logging into TurboTax's website between January 1 and April 30, 2019 actually clicked on the hyperlink to the Terms, which the district court used as support for the inference that many users did not notice the hyperlink.

Intuit appealed the decision to the Ninth Circuit.

The Ninth Circuit's Analysis

The Ninth Circuit reversed with instructions to compel arbitration.9 The Ninth Circuit agreed with the district court that an offeree is bound by an arbitration clause if "a reasonably prudent Internet consumer" would be put on "inquiry notice" of the "agreement's existence and contents."10 To make this determination the Ninth Circuit looked to "the conspicuousness and placement of the 'Terms of Use' hyperlink, other notices given to users of the terms of use, and the website's general design" in assessing whether a reasonably prudent user would have inquiry notice.11 The Ninth Circuit considered the issue before it a pure question of law because the material evidence consisted exclusively of screenshots, the authenticity of which was not disputed.12

The majority of the three-judge panel concluded that TurboTax's website provided sufficient notice to a reasonably prudent internet consumer of the Terms because: 1) TurboTax's website contained an explicit textual notice that clicking a "sign-in" button would act as a manifestation of the user's intent to be bound by the Terms; and 2) the relevant warning language and hyperlink to the Terms were conspicuous. Specifically:

- They were the only text on the webpage in italics;

- They were located directly below the sign-in button; and

- The sign-in page was relatively uncluttered.

The plaintiffs subsequently filed a petition for rehearing in front of the full Ninth Circuit. That petition was denied on October 2, 2020.

Implications

While Intuit ultimately prevailed on its motion to compel arbitration, the history of the case suggests and reinforces that some judges may go to great lengths to avoid sending consumer claims to arbitration.13As described in our alert regarding Meyer v. Uber Technologies, Inc., companies with consumer-facing products should ensure their methods of obtaining assent to online terms of service comply with best practices. Thoughtful design and presentation of online terms of use agreements, including choices of language, location, color, underlining, and font, all can reduce the risk of litigation over the enforceability of an arbitration provision within a terms of use. Please contact a member of Wilson Sonsini's technology transactions department or commercial litigation practice to discuss any questions that you may have regarding this decision or its implications.

[1] Arena v. Intuit Inc., No. 19-cv-02546-CRB, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 43296 (N.D. Cal. Mar. 12, 2020).

[2] Dohrmann v. Intuit, Inc., No. 20-15466, 2020 WL 4601254 (9thCir. July 16, 2020).

[3] Dohrmann v. Intuit, Inc., No. 20-15466 (9thCir. Oct. 2, 2020).

[4] Arena v. Intuit, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 43296, at *9 (citing Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble Inc., 763 F.3d 1171, 1175 (9th Cir. 2014)).

[5] Arena v. Intuit, 2020 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 43296, at *9 (citing Windsor Mills, Inc. v. Collins & Aikman Corp., 25 Cal. App. 3d 987, 101 Cal. Rptr. 347, 351 (Cal. Ct. App. 1972)).

[6] Id. at *10 (citing Colgate v. JUUL Labs, Inc., 402 F. Supp. 3d 728, 764 (N.D. Cal. 2019)).

[8] Id. at *11 (citing Meyer v. Uber Techs., Inc., 868 F.3d 66, 79 (2d Cir. 2017)).

[9] Dohrmann v. Intuit, Inc., 2020 WL 4601254.

[10] Dohrmann v. Intuit, Inc., 2020 WL 4601254, at *1 (citing Long v. Provide Commerce, Inc., 200 Cal. Rptr. 3d 117, 122 (2016)).

[11] Dohrmann v. Intuit, Inc., 2020 WL 4601254, at *1 (citing Nguyen v. Barnes & Noble Inc., 763 F.3d at 1177).

[12] Id. at *2. The court did not consider the percentage of users who actually clicked on the Terms, implicitly concluding that such fact was irrelevant to the analysis.

[13] Please see Wilson Sonsini’s alert regarding Scotti v. Tough Mudder here for more information.

Contributors

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility