By Elise N. Zoli, Peter Mostow, Todd Glass, Scott Zimmermann, Brady Berg, Robert G. O’Connor, Devon Wilson, Elizabeth Butscher, Claire Yerman, and Max Learner

The U.S. is a textbook innovation economy. Exceptional dynamism—intellectual and financial—has driven the country's sustainability sector, and with it domestic and global economic development. The current industrial revolution, unlike the original one, is not simply a race to extract resources; it requires the achievement of global prosperity in the face of ecological limits. As the groundwork for this revolution is laid, U.S. successes should be lauded, and U.S. setbacks addressed without alarmism.

Here, we assess one such setback—the United States Supreme Court's most recent climate decision (West Virginia v. EPA, issued June 30, 2022). The majority opinion is not a nod to American business and economic success. To the contrary, the engines of America's innovation economy, including Apple, Google, and Salesforce, all supported the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA’s) climate regulation, known as the Clean Power Plan.

Rather, the majority defends an industry with less than $19 billion in total market value or 19 days of Apple revenues (net sales). The majority does so by re-interpreting Congress's mandate to the EPA to identify, after taking into account the cost, public health, environmental, and energy considerations, the "best system of emission reduction."1 The majority focuses on the word "system" and divines that that term excludes reduced power plant operation (via advanced computing or AI), carbon attribute trading platforms, or really anything involving new technology, because "system" is limited to mechanical equipment or hardware directly bolted onto individual power plants. The majority's point of view is summed up in a single sentence: "[T]here are no particular controls a coal plant operator can install and operate to attain the emissions limits established by the Clean Power Plan." Ergo, no "system" and nothing to be done. To no avail, the dissent reminds the majority that the simplest of mechanical "systems," one that meets the majority's redefinition and underpins the EPA's plan to shift power production from coal to cleaner sources, is the on/off switch.

The majority cannot change the laws of supply and demand. Unsurprising given a superior levelized cost, utility-scale renewables have dominated new power plant capacity for more than a decade, representing 92 percent of new generating capacity in 2021. We do not have to remind most Americans that the transformation of our energy system and landscape is underway—wind turbines and solar arrays across our communities, and electric vehicles in our driveways. Today, we find ourselves in a new wave of talent migration and company formation, powered by willing investors and expanding in all directions, to bring decarbonization to sector after sector. And, mostly, U.S. innovative dynamism remains the vanguard of the global economy, benefitting us all.

This is not to say that the decision will have no detrimental effect. It complicates EPA's leadership, although that agency has long demonstrated creativity and resolve in the face of setbacks. It undervalues the will of most American businesses, investors, and consumers, which have already spoken and loudly in support of climate action and the new American economy. And, we are nothing if not testimony to the creativity and resolve of the American energy sector, a majority of which already use internal carbon pricing, including to drive low-carbon investment. For them, the climate innovation opportunity is more than its own reward.

Climate innovation underpins the new economy Americans want and need.

The U.S. is the 19th century origin species for modern innovation economies, a fact that has inured to the U.S. population's collective benefit. Innovation, grounded in new ideas (ideation) and technologies that translate into practical value, is a primary driver of long-term economic growth and prosperity. Competition in an open economic system allows innovation to flourish. This is not news to leading economists. In the 1950s, Nobel laureate Robert Solow determined that, within developed economies, "the largest contribution [to prosperity] came from something that can't be explained by population growth, a labor supply increase or a growing stock of equipment," but from technological innovation. Nobel laureate Paul Romer more recently echoed that "economic growth doesn't arise just from adding more labor to more capital, but from new and better ideas expressed as technological progress." Drs. Solow and Romer, and their peers, admonished that the U.S. should aim for that kind of improvement again.

The U.S. is, as an economy, taking Dr. Solow's and Dr. Romer's advice in advancing climate innovation. Again, some climate technologies are already ubiquitous, with the next generations of climate technologies waiting in the wings—in our National Labs, our universities, and the minds of our nation's teenagers. Last year, climate tech start-ups raised $53.7 billion globally, breaking investment records and driving new ideas forward. As of February 2022, $1 trillion in private capital is waiting to be invested in clean energy and climate risk solutions, with more than $50 trillion in assets under management now, including through the Climate Action 100+, committed to "net zero" or climate-action portfolios.

Investors are not alone. More than 400 companies, from Bayer to Walmart, signed an open letter to President Biden, championing the administration's climate action and encouraging halving greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Explicit in the letter is the understanding that an emissions reduction target, e.g., the plan, would "spur a robust economic recovery, create millions of well-paying jobs, and allow the U.S. to ‘build back better' from the pandemic." Implicit is the understanding that regulation, far from destabilizing commerce, can and often does function as a catalyst, accelerating the R&D, commercialization, and scaling investment that drives innovation and economic prosperity.2 Unwilling to wait, voluntary corporate procurement efforts led to record installations of 11 gigawatts (GW) of clean energy in 2021 and 6.5 GW announced as of late April.

U.S. climate innovation will continue to thrive.

Fear that a Supreme Court decision will disrupt this new economy is understandable.

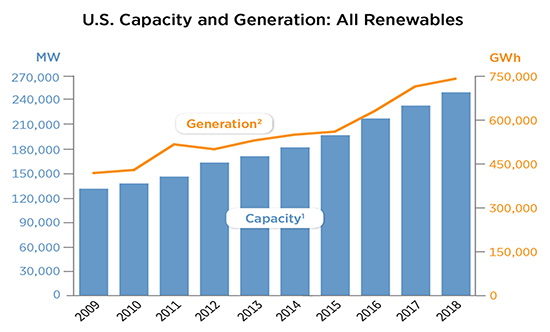

However, all indications are to the contrary. The Court's previous efforts to stall the EPA's climate regulation, which have flooded dockets since 2015, have had no discernable effect on U.S. renewables sector growth. In 2016, the Court stayed the plan, which likewise produced not a blip in renewables deployment nationally. Rather, installation of renewables capacity and generation continued apace, with a strong growth trajectory over the decade in which no plan has existed:

Source: 2018 Renewable Energy Data Book, https://www.nrel.gov/news/program/2020/latest-data-book-shows-us-renewable-capacity-surpassed-20-for-the-first-time-in-2018.html

This is not to say nothing is lost. Could the EPA's plan have accelerated development and deployment of climate innovation in a handful of states that otherwise will now more easily try to opt out of the new economy? Probably. And, because West Virginia's emissions are to our collective environment, the majority-authorized freedom to continue pollution loading in the short term (or what a pioneering financial institution calls WILD, or "Wasteful, Idle, Lazy and Dirty" activities) will continue—until customers and investors demand otherwise, or West Virginia sees the light.

That day is already here. Americans overwhelmingly want clean energy, and U.S. companies and investors have responded to consumer demand by disproportionately backing clean energy development across the U.S. This means that even states that may not embrace sustainability as a mission are nonetheless advancing the new economy at lightning speed based on economic merits. Texas, Iowa, Oklahoma, and Kansas lead the nation for the most installed wind capacity (2021). And, despite the Russian invasion of Ukraine, energy investment in 2022 remains overwhelmingly climate committed. It also means that American purchasing behavior is shifting industry in ways that might have been unthinkable a decade ago. Traditional Detroit truck manufacturers, including GM, Ford, and Hummer, have reported well over 300,000 orders, and Tesla reports more than a million, an unprecedented adoption level unlikely to be dimmed at current gas and diesel prices. Organic food is increasingly on our collective shelves, with an 82 percent average adoption rate nationally, showing significant incremental growth each year in the last decade, despite growing pains. Plant-based food growth charted three times total food retail sales (2021). Even fashion is shifting its focus and practices. While the sustainable economy is just beginning to gain steam, no sector is likely to remain untouched or untouchable by a climate-centered or sustainable focus.3

Discussing what Americans want can blunt discussion of what America needs, which is a renewed focus on U.S. innovation leadership, premised on committed R&D, and with it U.S. competitiveness on a global basis. The majority opinion in West Virginia doubles down on a seeming belief, unsupported by data, that the American economy will coast along, the coal industry should be saved despite its inability to compete, that leadership is inherited, not earned, and that innovation is practiced by some people in Silicon Valley, not all of us, acting with a shared sense of mission, bringing our considerable collective purchasing power to bear. We can and should correct that confusion, while there's still time.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the view of the firm or its clients.

[1] Under the relevant section, 42 U.S.C. 7411, the EPA’s Clean Power Plan involved reductions in power plant inefficiency, increased use of natural gas over coal, and increased use of renewable or non-climate polluting source.

[2] Regulatory certainty has underpinned corporate climate advocates for more than a decade, but current corporate purchasing behavior suggests product or service differentiation may be closer to the truth. New Chinese environmental regulation allows a starker analytical perspective. See, e.g., Q. Liu, et al., “Research on the Impact of Environmental Regulation on Green Technology Innovation from the Perspective of Regional Differences,” Sustainability (2022), 14, 1714 (positive effective on innovation); B. Wu, et al., “Environmental regulations and innovation for sustainability? Moderating effect of political connections,” Emerging Markets Review (2022) (assessing 4.924 private Chinese companies, formal and informal regulatory pressure have a positive effect on green technology development).

[3] Note from the authors: It is tempting to wonder aloud whether the long hair, loud music, and ripped jeans of a sustainable economy are too much, too fast, for the Court’s conservative cohort. Only hindsight will tell, but even today the setting echoes the film Pirate Radio, with actors Philip Seymour Hoffman and Bill Nighy shaking Kenneth Branagh’s legalistic machinations to silence a different form of emerging innovation—rock’n’roll.

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility