The EU’s rulebook on cooperation among competitors, which has been in place for over a decade, has recently undergone a revision with the European Commission (EC) adopting a new framework on June 1, 2023, that includes:

- updated and revised guidelines on horizontal cooperation agreements (Revised Guidelines),1 which set out the EC’s views on the application of EU competition law to various forms of cooperation among competitors, including joint production/purchasing, commercialization, R&D, specialization, information sharing, and, notably, joint sustainability initiatives,

- two revised Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations that maintain existing safe harbors for certain R&D agreements (Revised R&D HBER)2 and specialization agreements (Revised Specialization HBER),3 and

- an accompanying set of Q&As.4

While most changes bring the framework up to date with the EC’s decisional practice and European Courts’ judgments of the past decade, the Revised Guidelines break new ground on sustainability. In this alert we discuss in depth the new guidance on sustainability agreements and provide an overview of the main changes/updates in other areas.

Revised Guidelines: New Sustainability Chapter

In a new chapter devoted to this subject, the EC signals an accommodating stance for joint initiatives pursuing sustainability objectives. This aligns competition policy with the European Green Deal strategy to transition to a sustainable, net-zero carbon economy, as part of which the EC has been adopting numerous new regulations, including on sustainability disclosures, supply chain due diligence, carbon border tax, etc.5 According to the EC Vice President and Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager “[the]…guidance is a key tool to push forward the green and digital transitions.”6

In terms of scope, the guidance applies to agreements among competitors pursuing sustainability objectives (sustainability agreements). Sustainability objectives are broadly defined and include “…addressing climate change, reducing pollution, limiting the use of natural resources, upholding human rights, ensuring a living income, fostering resilient infrastructure and innovation, reducing food waste, facilitating a shift to healthy and nutritious food, ensuring animal welfare, etc.”7 However, while broad, the notion of sustainability in the Revised Guidelines covers only the “E” (environmental) and “S” (social) in the concept of “ESG,” which should be kept in mind by businesses considering “G” (governance) focused joint initiatives.

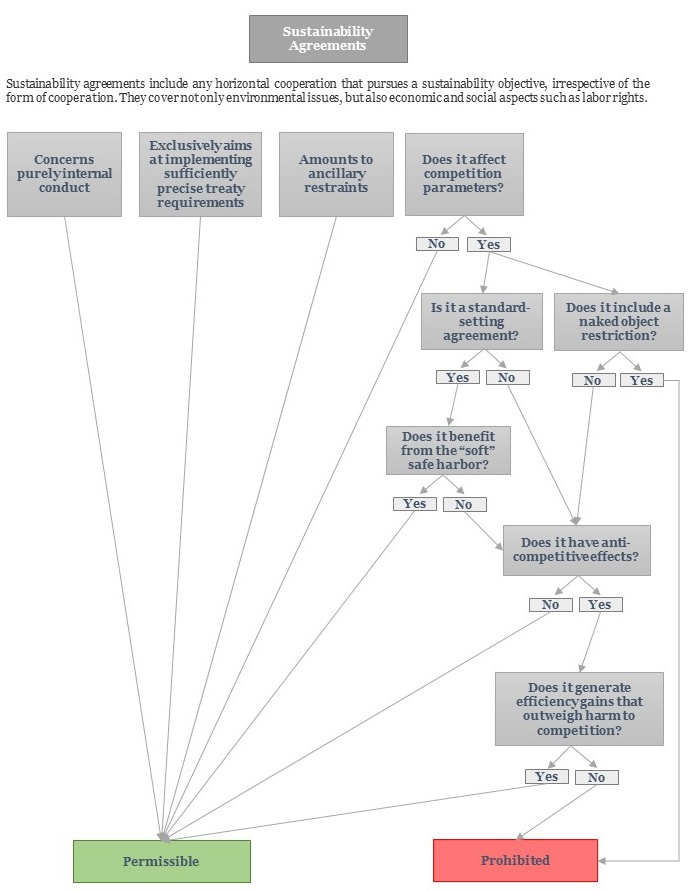

Addressing the key question of whether EU competition rules (Article 101 of the Treaty on the functioning of the EU, TFEU) stand in the way of sustainability agreements, the guidance shows various paths to compliance depending on the type and nature of the conduct involved. Accordingly, they can be broadly categorized into i) agreements unlikely to raise competition concerns or falling outside of competition rules, and ii) agreements whose negative impact on competition (including prices and choice) is outweighed by efficiency gains.

Sustainability Agreements Unlikely to Raise Competition Concerns

First, the EC remarkably commits that it will not take enforcement action against sustainability agreements whose exclusive aim is to ensure compliance with “sufficiently precise requirements or prohibitions in legally binding international treaties, agreements or conventions, whether or not they have been implemented in national law”8 [emphasis added]. These treaties can be related to areas such as fundamental social rights or prohibitions on the use of child labor, the logging of certain types of tropical wood, or the use of certain pollutants.9 For instance, the United Nations (UN) Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention establishes a requirement to “prevent the engagement of children in the worst forms of child labor.”10 Under this Convention, the worst forms of child labor include any forced or compulsory labor.11 In this context, an industry-wide agreement banning the production and/or marketing of goods made using children’s forced labor might fall within the framework of this exception.12 In another area, the Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution imposes a requirement to “undertak[e] to develop the best policies and strategies […] in particular by using the best available technology which is economically feasible and low- and non-waste technology” to combat air pollution.13 On this basis, for example clothing brands could develop a strategy to eliminate microfiber pollution from processes across the textile value chain. More recently, the UN formally adopted the High Sea Treaty which defines protected marine areas in international waters, in which activity could occur but only “…provided it is consistent with the conservation objectives,” i.e., provided it doesn’t damage marine life.14 On this basis, major retailers could agree to reduce/eliminate their offering of seafood coming from these protected marine areas and caught in a manner inconsistent with the conservation objectives.

Second, the EC creates a soft safe harbor15 for agreements that aim to achieve sustainability objectives through the creation of sustainability standards that participating businesses have to comply with (sustainability standardization agreements), provided a number of cumulative conditions are met.16 The conditions include, inter alia, that the procedure for setting the sustainability standard is transparent and open for participation, the participation is voluntary, the participants are free to adopt a higher standard and do not exchange Commercially Sensitive Information (CSI), and the agreement doesn’t lead to significant increase in price or reduction in product choice (or the combined market share of the participating companies does not exceed 20 percent on any relevant markets affected by the standard).17 The Revised Guidelines clarify that a price increase resulting from the standard can be considered as insignificant where “the product covered by the sustainability standard represents only a small input cost for the product.”18 In this context, the EC gives the example of a hypothetical “Fair Clothing” standard adopted by clothes manufacturers and retailers that requires respecting minimum wage for all workers involved in clothes production. While leading to a 20 percent increase in average wages to workers in developing countries, the standard’s estimated effect on final price of clothes ranging from -0.5 percent to 0.8 percent would be considered insignificant, given the insignificance of wages as a component of final price and possible improvements in productivity resulting from higher wages.

Third, the guidance clarifies that the following would fall outside the scope of EU competition rules:

- Agreements that do not concern companies’ economic activity but merely relate to their internal corporate conduct, such as eliminating single use plastics from the workplace, adjustments in ambient temperature or reduction in document printing, would fall outside the scope. This is despite the fact that some of these agreements would likely have an indirect impact on prices.

- Agreements to set up databases with information about suppliers’ sustainability credentials, as long as they do not restrict the ability to deal with such suppliers.

- Agreements to engage in industry-wide, awareness-raising campaigns.

- Ancillary restraints, i.e., any restriction of competition that is directly related to and necessary to the implementation of an agreement that has neutral or positive effects on competition.19 The main agreement must be impossible to carry out without the ancillary restraint, i.e., not just more difficult to implement or less profitable without the ancillary restraint.20

Sustainability Agreements Likely to Benefit from an Efficiency Exemption Under Article 101(3) TFEU

Sustainability agreements that negatively impact competition (including standardization agreements outside the soft safe harbor) can benefit from an exemption under Article 101(3) TFEU if, inter alia, they generate efficiencies, which outweigh the harm to consumers. While the guidance makes it clear that an exemption under Article 101(3) is available for both agreements that restrict competition by effect and by object, the latter is traditionally considered unlikely given the serious nature of the harm involved in agreements restrictive by object. Therefore, it is encouraging that the EC, reflecting the latest Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) case law on the concept of restrictions by object, recognizes that where parties can demonstrate that the main objective of their agreement is the pursuit of a sustainability objective, such an agreement may be assessed as restrictive by effects, even if it may affect core competition parameters such as price (unless the agreement is a mere guise for price fixing).

As to what qualifies as an efficiency gain and how to determine if it outweighs the harm caused by the agreement, the EC broadens the approach to the exemption conditions for sustainability agreements. Efficiency gains can take various forms, ranging from better quality products, less pollution, cleaner production and/or distribution technologies, to consumer choice improvement.21 The EC can credit not only efficiencies accruing to users of the relevant products but also “collective benefits,” i.e., benefits for a wider section of society that occur irrespective of the consumers’ individual appreciation of the product or its enhanced value to them.22 In assessing collective benefits, the EC will be able to consider them insofar as there is a significant overlap with the customers that are negatively affected by the agreement. For example, “drivers purchasing less polluting fuel are also citizens who would benefit from cleaner air, if less polluting fuel were used. To the extent that a substantial overlap of consumers (the drivers in this example) and the wider beneficiaries (citizens) can be established, the sustainability benefits of cleaner air can be taken into account, provided that they compensate the consumers in the relevant market for the harm suffered.” Presumably the harm suffered by the drivers in this example would be increased costs of fuel. This shows the potential significance of the collective benefits concept, provided that parties can support their claims with sufficient evidence, such as reports by public authorities or academic institutions, which according to the guidance are of particular value.

Informal Guidance

The Revised Guidelines explicitly mention that the EC is committed to provide informal guidance on sustainability initiatives under the EC’s Informal Guidance Notice,23 which gives companies operating in the EU the opportunity to obtain a guidance letter from the EC as to whether their conduct is compliant with EU competition rules.24 This is an encouraging statement by the EC for companies seeking to launch sustainability initiatives or enter into industry alliances, giving them an opportunity to seek clarity and comfort on whether the initiatives would comply with EU competition rules.25

Revised Guidelines: Other Notable Updates

Exchange of Commercially Sensitive Information26

CSI covers any information that is likely to influence competitors’ commercial strategy, i.e., information that is important for a company to maintain or improve its competitive position on the market. It includes, for instance, future product prices, granular information such as sales by country, or confidential information with respect to product launches. In contrast, historical information, aggregated sales information, or publicly available information, is generally not commercially sensitive.

Exchanges of CSI that are capable of removing uncertainty about future market conduct of the participants (e.g., intended prices or quantities) carry the highest antitrust risk. They are typically considered as restrictive by object and treated on par with cartel conduct by European agencies. Exchanges of other types of CSI are typically assessed with regard to the effects of the exchange on competition.

Indirect CSI exchange (i.e., information exchanged via a third-party service provider such as a trade organization, a common manufacturer, an online intermediary platform, or a shared algorithm) can also be found anticompetitive by the EC.27 This is the case when a company expressly or tacitly agrees with a third party to share CSI with its competitors or could reasonably have foreseen such information exchange. For instance, the aggregation of CSI into a pricing tool offered by an IT company to which competitors have access, would carry high antitrust risk.

Unilateral disclosure of CSI (e.g., via chats, emails, phone calls, meetings, or input in an algorithm) can be problematic if the recipients either requested it or accepted it, whether expressly or implicitly by not objecting to the unilateral disclosure.28

Public announcements (e.g., via a post on a website) of CSI relating to the future market behavior of a company (e.g., future prices, output, and/or commercial strategy) can also be problematic, in particular when the announcement is followed by public announcements by other competitors.29 The fact that the company making the public announcement has previously published similar information (e.g., on its website) does not automatically mean that a subsequent non-public exchange would not be a violation of competition rules. The Revised Guidelines provide examples of illegal unilateral announcements—for instance, in an industry where it is considered as public knowledge that supply costs are rising, companies must not “publicly evaluate their individual response to these rising costs, as doing so reduces uncertainty regarding their conduct on the market.” Likewise, company representatives should not comment on the company’s strategies on how to react to changing market conditions.

To date, even if price signaling practices have been investigated several times and increasingly in the EU by the EC and national competition authorities, cases involving pure price signaling have mainly resulted in commitment decisions where no infringement was established.30

Bidding Consortia

The Revised Guidelines clarify the treatment of bidding consortia (i.e., situations where bidders cooperate in a public or private procurement tender) based on recent EC decisional practice.31 Bidding consortia should not amount to bid rigging if joining the parties’ capabilities allow them to participate in a tender that they could not realistically carry out individually. Even if the parties could independently participate in the tender, they could benefit from an exemption, as any other horizontal cooperation, subject to restrictive conditions (such as the existence of efficiency gains).32

Network Sharing Agreements

The Revised Guidelines introduce a new section on network sharing agreement, i.e., agreements on the sharing of mobile telecommunications network infrastructure, operating costs, and subsequent upgrade and maintenance costs.

The EC clarifies that network sharing agreements meeting a set of cumulative restrictive criteria are prima facie unlikely to raise competition concerns. These criteria include, inter alia, that the parties maintain independent retail and wholesale operations, maintain the ability to follow independent spectrum strategies, and do not exchange CSI.33

Revised HBERs: Safe Harbor for Certain R&D and Specialization Collaborations

The HBERs were first adopted in 2010 and 2011 to create safe harbors for certain types of horizontal agreements. Under the regime, certain agreements that would normally fall within the scope of competition rules, benefit from an exemption if they meet cumulative conditions, including combined market share thresholds.34

The HBERs cover joint R&D, exploitation of technology resulting from R&D, specialization agreements, as well as other types of agreements (such as production, purchasing, commercialization, standardization, and information exchange). For instance, and subject to the conditions of application, the block exemption covers agreements between companies to combine their R&D efforts in a joint venture which will develop the prototype of the first company and will then produce a new component and supply it to both companies, which will commercialize it independently.35

Even if the parties to an agreement do not meet the market share thresholds, their agreement can be exempted if it results in efficiency gains and meets other conditions of Article 101(3) TFEU. This can be the case, for instance, when engineering companies producing vehicle components set up a joint venture to combine their existing R&D efforts to improve the performance of an existing component.36 An exemption is more likely to be granted if there are other significant innovative competitors on the market, if the component subject to the joint venture has a short life cycle, and if the parties will continue to manufacture and sell the component independently.

This exemption is not available to agreements containing so-called “hardcore restrictions,” such as output or sales limitation, or price fixing.37 In addition, some obligations that are part of agreements benefiting from the safe harbor can be excluded from the scope of the safe harbor (e.g., obligation not to grant licenses to third parties to produce the contract product).38

The Revised HBERs are built upon their predecessors and maintain the benefits of the exemption. The scope of their safe harbor is extended, for instance, to all types of specialization and production agreements concluded by more than two parties.39 On the other hand, the Revised HBERs now give the EC and national competition authorities the power to withdraw the benefit of the exemption on a case-by-case basis.40 This might cover, in particular, R&D agreements that are likely to restrict innovation, even if the parties to the agreement are not competitors on existing products or technologies.

Wilson Sonsini Insights

There is growing acceptance by several global competition agencies that industry collaboration required to achieve genuine sustainability goals could be permitted by antitrust rules, especially in Europe. For instance, the UK Competition and Markets Authority is positioning itself as the sustainability cooperation-friendly regulator and recently issued for consultation draft guidance to show how businesses can pursue green cooperation without fear of infringing UK competition law.41

At the EU level, the Revised Guidelines present an encouraging shift towards a more accommodating approach to sustainability initiatives. The EC is sending a positive signal to companies considering collaborations motivated by sustainability objectives by creating an opportunity for discussion on the pro- and anticompetitive effects of these collaborations and showing several paths to antitrust compliance. Furthermore, to help address any uncertainty that firms may have about planned sustainability initiatives, the EC is committed to providing informal guidance by way of guidance letters.

However, despite the relaxation at the European level, there remains a significant uncertainty for sustainability collaborations that are global in scope. In particular, while U.S. Federal agencies have not indicated that pursuing sustainability collaborations was an enforcement priority, they made clear that such collaborations are not exempted from antitrust laws.42 In addition, some Members of Congress and state Attorney Generals have advocated for greater antitrust scrutiny of industry-wide sustainability initiatives.

Firms considering entering into sustainability collaborations should engage with antitrust counsel at an early stage to design initiatives that are antitrust compliant in any jurisdictions affected by them.

For more information, please contact Jindrich Kloub or any member of the firm's antitrust practice.

[1]See EC Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 TFEU to horizontal co-operation agreements, available here.

[2]See EC Regulation (EU) on the application of Article 101(3) of the Treaty on the functioning of the EU (TFEU) to certain categories of research and development agreements, available here.

[3]See EC Regulation (EU) on the application of Article 101(3) TFEU to certain categories of specialization agreements, available here.

[4]EC, Questions and Answers on adoption of the new Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations and Horizontal Guidelines, June 1, 2023, available here.

[5]In particular, the EU recently enacted five laws aiming to ensure that EU policies are in line with EU’s climate targets of reducing net greenhouse gas emissions by 55 percent by 2030 and achieving “net zero” emissions by 2050. See Wilson Sonsini Alert, European Council Adopts New “Fit for 55” Laws, May 30, 2023, available here.

[6]See EC Press Release, Antitrust: Commission adopts new Horizontal Block Exemption Regulations and Horizontal Guidelines, available here.

[7]Revised Guidelines, para. 517.

[10]UN Worst Forms of Child Labor Convention, 1999, Article 7(2)(a), available here. The Convention was ratified in 2020 by all UN Member States.

[12]In this area, the EC recently presented a proposal for a regulation to prohibit products made using forced labor, including child labor. See European Parliament Briefing Paper, Proposal for a ban on goods made using forced labor, February 2023, available here.

[13]1979 Convention on Long-Range Transboundary Air Pollution, available here. It created a regional framework applicable to Europe, North America, and Russia.

[14]UN, General Assembly, Draft agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction, March 3, 2023, available here. The Agreement will come into force after 60 countries ratify it. This is expected by 2025. See Greenpeace, UN Ocean Treaty formally adopted, as the race to ratification begins, available here.

[15]A “soft” safe harbor protects only from an action launched by the EC and does not bind national courts or competition authorities, unlike a ‘hard’ safe harbor created by way of a Block Exemption Regulation.

[17]The EC clarifies that the 20 percent market threshold does not only refer to the specific products covered by the agreement, but also to all products in the relevant market. See Revised Guidelines, footnote 384.

[19]Ibid., para. 34. See also CJEU, C-382/12 P, Mastercard & others v. EC, Judgment of September 11, 2014, para. 89, available here. See also 2010 R&D HBER, Article 2(3), and EC Notice on restrictions directly related and necessary to concentrations (2005/C 56/03), available here.

[20]CJEU, C-382/12 P, Mastercard & others v. EC, Judgment of September 11, 2014, para. 91.

[21]Revised Guidelines, paras. 557-559.

[23]EC Notice on informal guidance relating to novel or unresolved questions concerning Articles 101 and 102 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union that arise in individual cases (guidance letters), available here.

[26]Revised Guidelines, Chapter 6.

[28]Ibid., paras. 396-400. See also CJEU, Case C-74/14, Eturas and Others, judgment of January 21, 2016, paras. 38 and seq.

[29]See 2011 EC Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to horizontal co-operation agreements, para. 63.

[30]See e.g., Case AT.39850, EC Decision of July 7, 2016, related to container shipping companies. At the national level, see Case 13.0612.53, Dutch Competition Authority Decision of January 7, 2014, regarding the mobile network operator companies, and Irish Competition Authority Decision of February 8, 2022, related to private motor insurance companies.

[34]The combined market share must not exceed 25 percent for the Revised R&D HBER and of 20 percent for the Revised Specialization HBER. See Revised R&D HBER, Article 6(1)(a), and Revised Specialization HBER, Article 3(1).

[35]Revised Guidelines, para. 168.

[37]See Revised R&D HBER, Article 8, and Revised Specialization HBER, Article 5.

[38]Revised R&D HBER, Article 9. The Revised Specialization HBER has no equivalent.

[39]Revised Specialization HBER, Article 1(1).

[40]See Revised R&D HBER, Article 10, and Revised Specialization HBER, Article 6.

[41]U.K. Competition and Markets Authority, Draft guidance on the application of the Chapter I prohibition in the Competition Act 1998 to environmental sustainability agreements, February 28, 2023, available here.

[42]Federal Trade Commission Chair Lina Khan’s Statement, Senate Judiciary Subcommittee Hearing, September 20, 2022, available here.

Contributors

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility