The metaverse presents exciting new opportunities for brands to engage a new audience through interactive virtual environments and immersive experiences, including with virtual products that cross the digital divide. Many luxury goods companies, for example, now offer NFTs and other digital items under flagship brands that correspond with real-world products in an effort to drive engagement and instill brand loyalty among these new (and generally younger) consumers. Although there are still uncertainties as to how this new space will take shape, a recent jury verdict in the case of Hermès International, et al. v. Mason Rothschild, from the Southern District of New York,1 offers some guidance as to how courts may approach metaverse-related branding issues.

Shifting Legal Landscape

With new opportunity comes new risk. Brand presentation in the metaverse may diverge from consumers’ expectations with real-world physical products. In these virtual spaces, third-party content creators at times draw inspiration from or make use of brand owner intellectual property without brand owner permission. Where a more liberal view of fair use can converge with new digital incarnations of analog products, blurry legal boundaries create ripe conditions for misunderstanding and conflict. Brands should be aware of the shifting legal landscape around IP use in the rapidly growing metaverse.

Hermès v. Rothschild

There have been limited indications of how brand protection in the metaverse will be interpreted by courts. However, one recent case—involving a trademark infringement claim by the iconic luxury goods purveyor Hermès, known for its Birkin handbag, against digital “artist” Mason Rothschild—provides useful guidance for brand owners and content creators seeking a better understanding of the limits of fair use in the metaverse.

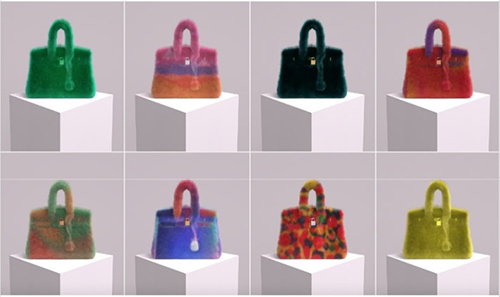

Credit: Mason Rothschild/MetaBirkins2

The case centered on a series of digital works created by Rothschild called “MetaBirkins”: look-alikes of the Hermès Birkin bags, which Rothschild described as a “fanciful interpretation of a Birkin bag” that provides social commentary on the fashion industry.3 Importantly, Rothschild’s digital works are commercial in nature; he marketed and sold the products on NFT marketplaces, and the first virtual Birkin sold for $42,000—approximately the same retail price as a physical Birkin bag.

Rothschild argued that his works constituted “artistic expression” that should be shielded from Hermès’ allegation of trademark infringement based on fair use principles deriving from the First Amendment.4 He advocated for application of the speech-protective test set forth in Rogers v. Grimaldi, which holds in general terms that a work of artistic expression constitutes fair use and is a defense to a claim of trademark infringement unless the work explicitly misleads as to the source of the work.5 Hermès, by contrast, advocated for a different standard focused on the general test for trademark infringement, contending that Rothschild’s MetaBirkins were plainly not artistic.6 On the preliminary point of which standard to apply, the court sided with Rothschild.

While holding that the Rogers test applied to Hermès’ trademark infringement claims, the court nevertheless denied Rothschild’s motion for summary judgment (and Hermès’ cross-motion), finding that the test “does not offer defendants unfettered license to infringe another’s trademarks.”7 The court stated further that while “[w]orks of artistic expression …Â deserve protection,” they “are also sold in the commercial marketplace like other more utilitarian products, making the danger of consumer deception a legitimate concern that warrants some government regulation.”8 Further, “[i]in certain instances, the public’s interest in avoiding competitive exploitation or consumer confusion as to the source of a good outweigh whatever First Amendment concerns may be at stake.”9

In February, a federal jury in Manhattan found Rothschild liable for cybersquatting, trademark infringement, and dilution of Hermès’ trademarks for its Birkin bags.10 Hermès successfully argued that Rothschild’s MetaBirkins should not be protected because they were an attempt to profit off the goodwill associated with the fashion house’s famous BIRKIN marks and the Hermès brand. Rothschild’s argument that he did not intend to mislead customers as to the source of the MetaBirkins fell short—despite pointing to a disclaimer on the MetaBirkins site and heavy reliance on artistic expression under the First Amendment.

The Rothschild decision should help guide brand owners. First, the divide between virtual goods and tangible products is less significant than some may have expected. Trademark rights extend into the metaverse when there is some evidence that the senior trademark user could naturally expand its goods and services into the virtual world. Even without a trademark registration covering virtual goods or use in the virtual world, companies may still have an enforceable trademark right over a metaverse copycat if virtual items are within the brand owner’s natural zone of expansion. Second, the court’s reliance on the Rogers test implies that other NFTs or virtual goods could be considered artistic works that are protected under the First Amendment.11 In fact, the Rothschild court seemed to accept that the MetaBirkins were artistic works (which is met under Rogers “unless the [use of the mark] has no artistic relevance to the underlying work whatsoever”).12 Even still, the commercial element of the NFTs in this case—and Rothschild’s express invocation of the Birkin brand and imitation of the bags—resulted in a finding in favor of Hermès.

Another lesson may be found in Hermès’ apparent failure to offer virtual goods or proactively introduce its brand into the metaverse at the same rate as similarly situated brands. By entering the metaverse, a brand known largely for physical goods can create a broader recognition of the brand in the minds of consumers across various fields of use and, by consequence, strengthen the brand itself, widen its scope of protection, and deter potential infringers. In Hermès’ case, while it won an initial legal victory after significant effort, it apparently still has more work ahead: Rothschild has taken his case to social media, casting aspersions on Hermès’ respect for artists, and filed a motion with the court for a new trial.

Regulatory Guidance

Regulators have taken note of the increased need for guidance in this new space. Last year, the FTC announced plans to revise its online advertising guides in the metaverse and virtual reality spaces.13 The FTC’s online disclosure guide focused on digital advertising was first released in 2000 and was last updated nearly a decade ago. Revised, metaverse-centric guidelines will hopefully bring increased clarity.

Key Takeaways

Companies should monitor third-party use of their intellectual property in the digital world—even if their core brand is not rooted in virtual spaces. Moreover, even with the Rothschild decision demonstrating that a significant metaverse presence is not required for enforcement in the realm, companies should thoughtfully consider intellectual property and brand-building strategies to increase enforcement success in this virtual frontier.

For more information about the Rothschild decision, metaverse-related branding issues, or any related matter, please contact Aaron Hendelman, Brandon Leahy, Chloe Delehanty, or another member of Wilson Sonsini’s electronic gaming or trademark and advertising practices.

[1] Hermès International, et al. v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF No. 145.

[2] Hermès International, et al. v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 1-19 at 2.

[3] Hermès International, et al. v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 17 at 1.

[4] Hermès International, et al. v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 17 at 11-20.

[6] Hermès International, et al. v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 1 at 3.

[7] Hermès International v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 140 at 19.

[8] Id. (citing Rogers v. Grimaldi, 695 F. Supp. 112, 120-121 (S.D.N.Y. 1988)).

[9] Hermès International v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 140 at 19.

[10] Hermès International, et al. v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384 (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF 145; Hermès also requested injunctive relief, but the district court has yet to rule on that request (see ECF 168).

[11] The court’s instructions to the jury demonstrate that use of the Rogers test for artistic works carried over to trial. See Instructions of Law to the Jury, Hermès Int’l v. Rothschild, No. 1:22-cv-00384-JSR (S.D.N.Y. 2023), ECF No. 143, “Instruction 14” at 21-22 (“It is undisputed, however, that the MetaBirkins NFTs, including the associated images, are in at least some respects works of artistic expression, such as, for example, in their addition of a total fur covering to the Birkin bag images.”).

[12] Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994, 997 (2d Cir. 1989).

[13] https://www.ftc.gov/news-events/news/press-releases/2022/06/ftc-looks-modernize-its-guidance-preventing-digital-deception.

Contributors

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility