Beware of “Most Favored Nations” Clauses in Commercial Contracts

By Rob Parr

Imagine that your digital health company has developed a groundbreaking product. You are eager to monetize the product, so you sign non-disclosure agreements with several of the most well-known hospitals in the United States. You successfully demonstrate the product and some of the hospitals are interested in pursuing a commercial deployment. You receive a draft contract from each hospital setting out the terms of your potential deals. You begin scanning those documents and notice that one includes a “most favored nations” provision (as used below, an MFN)—a provision that requires your company to offer the applicable hospital your best prices for your product and the related services as compared to the prices you offer other companies in certain other transactions. You were not planning to make this kind of commitment and you are not sure how doing so could impact your business. What should you do?

Many digital health companies may face this dilemma at some juncture. Below we provide some guidance to help you think through what an MFN would mean for your business and certain issues to consider when negotiating MFNs.

Granting an MFN would impose certain operational burdens and risks on your company. Some of these would include the following:

- 1. Price Reductions. Your company may need to offer reduced prices under certain circumstances (e.g., competitive pressures require a price reduction or an important potential customer demands one). In these cases, your company would have to extend the reduced prices to any company that you granted an MFN. This can happen repeatedly, which could significantly impact your company’s revenues and corresponding enterprise value under certain circumstances.

- 2. Monitoring. To ensure MFN compliance, your company would need to implement and maintain procedures to monitor the prices that it charges for sales of its products and services. This can be a burdensome process under certain circumstances, such as when your company has a large or fluctuating customer base, and when your company’s pricing model is complex and differentiated from customer to customer. This can be a particularly challenging task when your company is a start-up or otherwise has limited personnel and resources.

- 3. Audits and Diligence. When your company grants an MFN to a counterparty in a contract, the counterparty often will include language in the contract that requires your company to document MFN compliance and that provides the counterparty with rights to audit those records. If the counterparty exercises the audit right and alleges that your company has breached the MFN, this could lead to a lawsuit and liability for monetary damages or otherwise prove costly to resolve through a negotiated settlement. Potential investors and acquirers also will closely scrutinize MFN compliance during the due diligence process. These parties may decrease the consideration for the applicable transaction or walk away from the deal altogether if they uncover MFN noncompliance and/or if MFN provisions would cover sales by the investor or acquirer itself (or any of its affiliated companies).

- 4. Antitrust. MFNs also potentially could violate applicable antitrust laws under certain circumstances. The penalties for certain antitrust violations can be severe, and antitrust laws vary across different jurisdictions, so MFNs should be reviewed by antitrust counsel to ensure compliance with applicable laws.

Despite the above operational burdens and risks, your company nevertheless may determine there are compelling business justifications for granting an MFN under certain circumstances. In these cases, your company should try to negotiate the narrowest MFN possible. Your success in this regard will depend on the applicable deal dynamics (e.g., the relative bargaining power of each party and your willingness and ability to spend time and resources on contract negotiations), but some issues you should focus on during negotiations include the following:

- 1. Covered Products, Services, and Transactions. As illustrated in the hypothetical above, MFNs typically require company A to offer its best prices to company B for sales of certain products and services as compared to the prices that company A offers for sales of those products and services in certain other transactions.

- a) Narrowly define the products and services that count for MFN purposes. Exclude your company’s future products and services, significant modifications to your company’s current products and services, and all products and services developed or sold by your company’s future investors or acquirers (or any of their affiliates).

- b) Narrowly define the other transactions that count for MFN purposes. Draft the MFN so that it covers other transactions that are substantially similar to the transaction in which you grant the MFN. Define specific factors that must be used to determine when the transaction in which you grant the MFN and another transaction would be deemed substantially similar and therefore count for MFN purposes. For example, some of these factors may include: i. the geographic territory where the applicable counterparty is principally located; ii. the period when the MFN remains in effect; iii. the market or field in which the applicable counterparty will exploit the products and services; and iv. the volume of products and services purchased. Exclude sales through distributors from counting for MFN purposes because accurately tracking the prices charged in those transactions can be complicated and difficult.

- 2. Duration. Draft the MFN so that it would no longer apply if the counterparty does not purchase at least a minimum volume of products and services during specified time frames. This helps guarantee your company at least a minimum amount of economic value in exchange for granting the MFN.

- 3. Contractual Protections. Negotiate other contractual protections to mitigate the operational burdens and risks related to the MFN. Among others, this should include seeking the following protections:

- a) Limiting recoverable damages for an MFN breach to direct damages only (i.e., damages that immediately and naturally result from the breach, as opposed to more consequential damages, such as lost profits);

- b) Qualifying any audit rights and related remedies the counterparty may insist on including in the contract (e.g., permitting audits during specified time frames up to a total number of audits, defining the materials subject to audits, requiring reasonable advance notice for audits, and capping or otherwise reasonably limiting your company’s obligation to pay for audits and related penalties when noncompliance is uncovered); and

- c) Including a dispute resolution procedure that requires the parties to collaborate in good faith to resolve MFN disputes before resorting to a more formal legal proceeding permitted under the contract (e.g., litigation or arbitration).

Conclusion. Engage counsel as soon as possible if you are considering whether to grant an MFN. Counterparties may propose MFN provisions that could significantly impact your business, and properly negotiating those MFNs and related contractual provisions requires careful review and precise drafting. Be on the lookout for MFNs when doing deals for the commercialization of your products and services, especially in deals with large counterparties with significant bargaining power. These counterparties often will require the use of their form contracts, and MFNs may be buried in the fine print (e.g., included in innocuous looking standard terms and conditions) or incorporated into the contract by reference to a document the counterparty has not provided for review (e.g., a reference to online terms). Please do not hesitate to contact your attorneys at Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati if you need assistance with an MFN provision.

URGENT/11 and Other Stories to Tell in the Dark

Cybersecurity Advice on How to Keep Your Digital Health Technology Safe from Hackers

By Morgan Brown

There is no denying the digital era is revolutionizing the health and wellness industry. Our digital health clients are at the forefront of this revolution, working every day to re-envision every aspect of the health industry. Building the future of healthcare in a digital framework, however, also entails a tremendous amount of responsibility to design products and services that are secure and capable of safeguarding our most sensitive data. While the future may be bright, we can’t forget that just like any technology company, digital health companies face real and pervasive cybersecurity threats and a constantly evolving threat landscape that requires vigilant monitoring and an agile response. This article focuses on the particular challenge of maintaining security by design when digital health companies incorporate third-party software into a product, as highlighted by the recent URGENT/11 discovery of 11 critical vulnerabilities in a widely used operating system.

Tremendous economies can be gained by incorporating off-the-shelf (OTS) software, as it avoids the resourceintense process of building it out yourself. Real-time operating systems (RTOS) is a type of OTS software used in a wide range of critical devices that need high accuracy and reliability, including digital health products, medical devices, and hospital networking equipment. As the URGENT/11 case study shows, however, incorporating OTS software is not without risk, as it requires a company to rely on a third-party vendor to manage and mitigate security threats and vulnerabilities related to that software.

Recently, the enterprise security firm Armis discovered 11 “zero-day vulnerabilities,” which are previously unknown security flaws in software that with no immediate remediation available. The 11 vulnerabilities were discovered in VxWorks, an operating system that is used by over two billion devices, including critical medical devices. Dubbed “URGENT/11,” these vulnerabilities in RTOSs incorporated IPnet, an implementation of network protocols that allow devices to connect to networks.1 Following publication by Armis of the URGENT/11 vulnerabilities, companies began issuing security warnings, including leading global medical device companies GE Healthcare, Philips, Drager, and BD. According to Armis, the URGENT/11 vulnerabilities enable hackers to infiltrate the devices and networks to enable Remote Code Execution, deny service, and leak information. To drive home the seriousness of these vulnerabilities, Armis researchers exploited URGENT/11 to reach remote code execution over Spacelabs’ Xprezzon patient monitor and demonstrated how this exploit could allow an attacker to alter vital readings, create false alarms, and gain full control over all information displayed on the monitor.2

URGENT/11 and the risks to the critical devices that contain these vulnerabilities highlight a highly disconcerting issue: health services that run on digital devices or platforms are vulnerable to cybersecurity risks, particularly where they connect to other devices, the internet, other networks, or to portable media, such as a USB. The devices that used the VxWorks operating system containing the URGENT/11 vulnerability are not isolated: two years ago, researchers Billy Rios and Jonathan Butts discovered a major vulnerability in the software driving two popular insulin pumps. To prove how deadly such a vulnerability could be, and how easily it could be exploited, they developed an app that could remotely target the insulin pumps and cause deadly effects, such as withholding insulin from the patient or delivering a lethal overdose. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also issued multiple safety communications regarding cybersecurity risks in implantable cardiac devices that provide pacing for irregular or abnormal heart rhythms, further highlighting the risk.3

URGENT/11 highlights that even where a digital health company has developed its own rigorous security environment, that plan should account for the use of OTS software, particularly if adapting OTS software to fit the digital health company’s specific needs makes it even more difficult to apply a security patch. Digital health is full of exciting innovation that can contribute to the benefit of society. However, the technology does not come without a very real and fear-inducing threat: cybersecurity vulnerabilities. The best way for any digital health company to be proactive about mitigating cybersecurity risks is to be diligent from the very beginning.

1 See Armis’ report: https://www.armis.com/urgent11/.

2 See Armis’ demonstration: https://www.armis.com/resources/iot-security-blog/urgent-11-update/.

3 See FDA Safety Communications: “Battery Performance Alert and Cybersecurity Firmware Updates for Certain Abbott (formerly St. Jude Medical) Implantable Cardiac Devices” (April 17, 2018), “Cybersecurity Updates Affecting Medtronic Implantable Cardiac Device Programmers” (October 11, 2018), and “Cybersecurity Vulnerabilities Affecting Medtronic Implantable Cardiac Devices, Programmers, and Home Monitors” (March 21, 2019).

HIPAA for Digital Health Entrepreneurs: Research

By Haley Bavasi

Welcome to the fourth installment in our series exploring the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) for digital health entrepreneurs. This series focuses on HIPAA topics that impact our digital health clients, particularly those who may be newly encountering health privacy. Having covered the basic framework of HIPAA, who it applies to, and outlining the Privacy and Security Rules, this installment will focus on an area of interest for many of our clients: How does HIPAA come into play when conducting research?

Even if you have determined that your company is not regulated by HIPAA, you may want to partner with an entity that is—e.g., a hospital, doctor’s office, academic medical center, or insurer—to conduct research. These entities are rich repositories of data as well as potential testing grounds for your product or service. They are, however, also “covered entities” under HIPAA and subject to its regulations regarding the appropriate use and disclosure of protected health information (“PHI”), which is discussed in detail below. The question is how can you, as a digital health company, partner with these HIPAA-regulated entities to conduct research that facilitates access to this data and allows you to test your product or service in the field? In this installment, we take a high level look at how to achieve this.1

Refresher: What is PHI and How Can It Be Used and Disclosed?

Before diving into the more nuanced weeds of HIPAA in the research context, it is helpful to take a step back and refresh the definition of PHI and the constraints around its use and disclosure (particularly because the definition of PHI doesn’t come in a neat package).

The HIPAA Privacy Rule protects all “individually identifiable health information” in any form or media, when that information is held or transmitted by a covered entity or its business associate. The Privacy Rule calls this protected information “protected health information” or “PHI.”

“Individually identifiable health information” is information, including demographic data, that relates to:

- the individual’s past, present, or future physical or mental health or condition,

- the provision of health care to the individual, or

- the past, present, or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual,

and that identifies the individual or for which there is a reasonable basis to believe it can be used to identify the individual.

Under the Privacy Rule, PHI may only be used and disclosed by a covered entity for “treatment, payment or operations” (commonly referred to as “TPO”) without obtaining further authorization from a patient. Very importantly, “research” is not a use or disclosure that falls into the TPO bucket. Therefore, a covered entity—e.g., the hospital, clinic, or insurer you would like to partner with—may not use or disclose PHI to you without a valid authorization from the patient or complying with one of the bases discussed below. Having a business associate agreement in place will not change the need to obtain authorization or meet one of the other criteria below.

Ways to Obtain Access to PHI for Research Purposes

Obtain a Valid Authorization

Individuals may always provide an “authorization” that permits a covered entity (or its business associate) to use or disclose the individual’s PHI in any manner outside of TPO, including research. The most common path to obtaining data from a research study is to obtain a HIPAA compliant authorization with the study informed consent, which ensures the covered entity/study site is permitted to share the data with you and anyone else you deem be appropriate. While it is the covered entity’s responsibility to collect the authorization, it is in your best interest to ensure any informed consent and authorization being presented to the participant clearly gives the covered entity the permission to share research data with you, and any other third parties as appropriate.

The elements of a valid authorization are described in the regulations, and require the document to:

- Meaningfully describe the information to be used/disclosed;

- Identify who can use or make disclosure;

- Identify who the information will be disclosed to;

- Describe each purpose of the requested use or disclosure;

- Contain an expiration date (“none” is sufficient for a research study, including creation of a database); and

- Contain certain required statements, including right to revoke and any exceptions and whether treatment can be conditioned on signing.

Once PHI is disclosed pursuant to a valid authorization, the information is no longer “PHI” subject to HIPAA if the receiving party is not itself regulated by HIPAA (i.e., is not a covered entity). Therefore, a non-covered entity, digital health company could further use and disclose the study information without the information being subject to HIPAA.

Note that individuals may withdraw their authorization at any during the research. However, the researcher may continue to use or disclose PHI already collected for purposes of completing the research (but would not permit further disclosure of new information after the individual withdrew consent).

Limited Data Set

Another avenue for obtaining information is through a “Limited Data Set” or “LDS.” As its name suggests, the LDS is a more limited subset of information. Specifically, it is PHI that excludes the following direct identifiers of the individual to whom the PHI relates, or the relatives, employers, or household members of that individual:

- Names;

- Postal address information, other than town or city, state, and zip code;

- Telephone numbers;

- Fax numbers;

- Electronic mail addresses;

- Social Security numbers;

- Medical record numbers;

- Health plan beneficiary numbers;

- Account numbers;

- Certificate/license numbers;

- Vehicle identifiers and serial numbers, including license plate numbers;

- Device identifiers and serial numbers;

- Web Universal Resource Locators (URLs);

- Internet Protocol (IP) address numbers;

- Biometric identifiers, including fingerprints and voiceprints;

- Full face photographic images and any comparable images.

An LDS can be a particularly useful alternative in retrospective studies where a digital health company only wants to look at data, and does not otherwise involve human subjects directly. To obtain an LDS from a covered entity, the recipient must enter into a “Data Use Agreement” or “DUA,” which is a specific type of agreement with parameters governed by HIPAA. For readers familiar with a business associate agreement, to contrast, the DUA is lighter in its obligations, and primarily:

- Establishes permitted uses/ disclosures and not authorize further uses/disclosures that would violate the Privacy Rule;

- Establishes who is permitted to use/receive the LDS;

- Requires the recipient to comply with first two points and to use appropriate safeguards;

- Further requires the recipient to report to the Covered Entity (CE) any use/disclose not under the LDS; ensure any other recipients agree to same restrictions; and not identify the information or contact the individuals.

De-Identified Information

A covered entity (or its business associate) can use PHI to create de-identified information, which is no longer PHI (as long as it is not disclosed with a code or other means to re-identify it) and can be disclosed to a third party for any purpose, including research. If the particular research project 1) involves only analysis of data, 2) can be accomplished through the use of de-identified data, and 3) the CE is willing to provide this data, this is a good choice because it is the lowest maintenance of all the options, requiring no additional agreement, consent or authorization. Note that 3) is always a consideration, because it may be a laborious process to actually remove all 18 identified to render PHI properly deidentified.

In order to determine whether this type of information would work for your project, take a look at what these identifiers are2 and consider whether, absent this identifying information, what is left is still valuable to your research.

Other Research-Specific Avenues to Access Data

There are several other avenues that are available for researchers to access PHI, but less commonly used among our clients. These options, as may be evident, are generally less practical, or just do not present themselves as ready options, but nonetheless are worth noting:

- Documented Institutional Review Boards (IRB) or Privacy Board approval—You may be able to obtain IRB or Privacy Board approval from an institution if the research: is no more than minimal risk; could not be practicably completed without waiver or alteration; and could not be practically conducted without access to the PHI.

- Activities “Preparatory to research”—Researchers may use PHI to identify, but generally not contact, potential subjects as long as the PHI is not removed from the CE’s site (although some allowance for remote access).

- Research on PHI of Decedents—Researcher may have completed using PHI of individuals but still requires certain information and representations be made to the CE.3

Up Next

On the way are more real-world examples and analyses of how HIPAA is impacting the digital health industry. Of course, if this has provoked questions about HIPAA, privacy in general, or anything digital health related, please reach out to your WSGR attorney for more information.

1 This is a high-level summary of a complex area of the law. If you are a digital health company embarking on a research study, the best advice is to consult with counsel to navigate these issues.

2 45 CFR 164.514(b)(2)(i).

3 45 CFR 164.512(i)(1)(iii).

A Window into the FDA’s Risk-Based Regulatory Approach for Clinical Decision Support Software

By Kathleen Snyder

On September 27, 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidance on several areas impacting digital health and digital health products including updated draft guidance on clinical decision support (CDS) software.

The new guidance provides a window into the FDA’s proposed risk-based regulatory approach to CDS software. For a digital health company, it is important to understand how your product’s clinical decision support software functions will be defined by the FDA and how the FDA may regulate them. It is also important to note that you can make comments on the FDA’s proposed guidance. Comments are due at the end of December 2019.1

What Is Clinical Decision Support?

As a digital health company, you should understand how the FDA defines CDS software functions and if/how your product incorporates them. In the proposed guidance, the FDA defines clinical decision support as:

Technology that provides health care professionals and patients with knowledge and person specific information intelligently filtered or presented at appropriate times, to enhance health and health care.2

Questions the FDA Will Ask in Regulating Clinical Decision Support Software

The FDA highlighted the following questions that it will ask in regulating CDS Software:

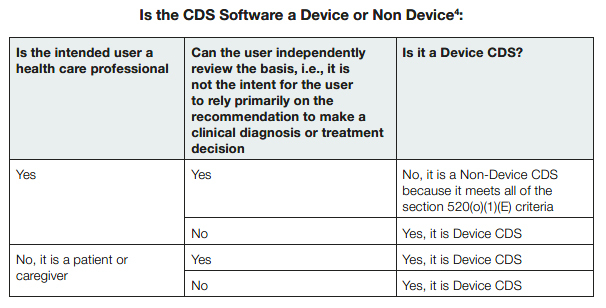

1. Is the CDS software a device or nondevice?

2. What is the relevant level of risk associated with the relying on the information provided by the CDS software?

If your product contains clinical decision support software, think about your FDA regulatory strategy by considering how these questions will apply to your product:

1. Is the CDS software a device?

The FDA will determine if the CDS software falls into the definition of a medical device, using the exemption criteria defined in 520(o)(1)(E) of the Food Drug and Cosmetic Act, as updated by the 21 Century Cures Act.3 The FDA included a helpful table to illustrate how it would determine whether the CDS software is a device:

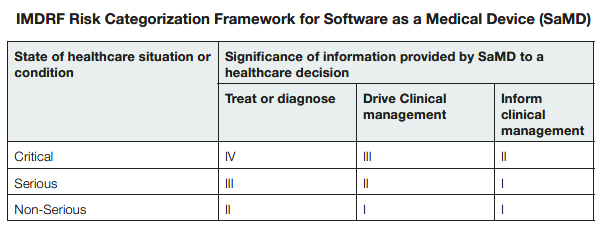

2. What is the relevant level of risk associated with the relying on the information provided by the CDS software?

The FDA will apply an international framework for risk assessment5 to the CDS software functions of a digital health product.

The FDA will look at the significance of the information provided by the CDS software to a healthcare decision. Specifically, the FDA will review whether the information will be used to treat or diagnose, to drive clinical management, or to inform clinical management.

The FDA will then look to the state of the patient’s healthcare situation or condition. Specifically, the FDA will review whether the information provided by the CDS software will be applied to a situation where the patient’s condition is critical, serious, or non-serious.

The FDA included a table6 that identifies the relevant level of risk based on the International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) Risk Categorization Framework for software as a medical device (SaMD) to illustrate how they will apply the risk assessment framework. The four categories (I, II, III, IV) are based on the levels of impact on the patient or public health where accurate information provided by the SaMD to treat or diagnose, drive, or inform clinical management is vital to avoid death, long-term disability or other serious deterioration of health.7 The categories are in relative significance to each other. Category IV has the highest level of impact, Category I the lowest.8

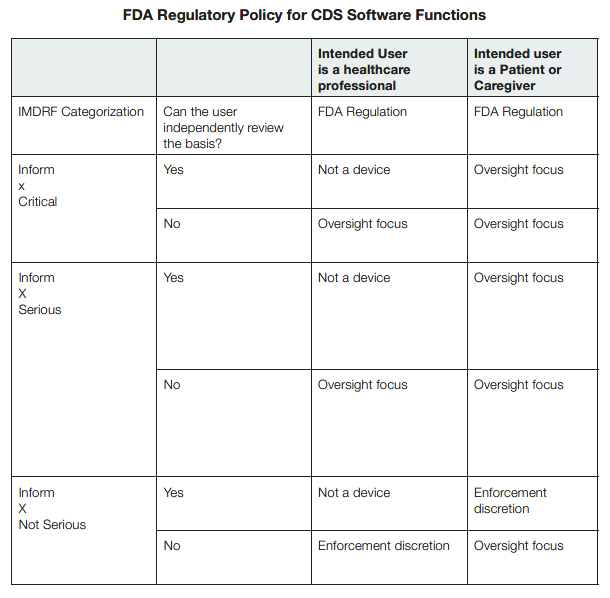

FDA Regulatory Discretion for CDS Software Functions

The FDA will determine the level of regulatory oversight of a digital health product’s CDS software based on whether the CDS software functions constitute a device and what category of risk assessment the information falls into. The agency’s oversight will also consider if the digital health product is intended for healthcare professionals or patients and caregivers.

Healthcare Professionals

The FDA intends to focus its regulatory oversight on device CDS software intended for healthcare professionals that are intended to inform clinical management for serious or critical situations or conditions and that are not intended for the healthcare professionals to be able to independently evaluate the basis for the software’s recommendations.9

Patients and Caregivers

The FDA intends to focus its regulatory oversight on device CDS software intended for patients that are intended to inform clinical management for a nonserious situation or condition and that are not intended for the patient to be able to independently evaluate the basis for the software’s recommendations.10

The FDA also intends to focus its regulatory oversight on Device CDS software intended for patients that are intended to inform clinical management for a serious or critical situation or condition, whether or not the software is intended for the patient to be able to independently evaluate the basis for the software’s recommendations.11

The FDA has indicated that it is not likely to enforce compliance with applicable device requirements if the CDS software is intended for patients or caregivers to inform or provide guidance for nonserious health conditions and the patient or caregiver using the device can independently review the basis for its recommendations, as the FDA has indicated that it considers such situations low risk.12

The FDA included a helpful table13 to illustrate how it would regulate the CDS software functions:

Conclusion

The FDA has provided a window into its risk-based regulatory analysis with proposed guidance. You can help prepare your FDA regulatory strategy by walking your product’s clinical decision support software functions through the FDA’s decision points by using its proposed charts.14

If you want to comment on the proposed guidance you have until the end of December 2019.15

1 You may submit comments and suggestions regarding the FDA draft guidance within 90 days of publication in the Federal Register of the notice announcing the availability of the draft guidance. Submit electronic comments to https://www.regulations.gov. Submit written comments to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. Identify all comments with the docket number FDA-2017-D-6569.

2 Page 8 of the FDA Guidance at https://www.fda.gov/media/109618/download.

3 Pages 6 and 7 of the FDA Guidance refer to the CDS functions excluded from the definition of device by section 520(o)(1)(E) of the FD&C Act. Excluded software functions must meet all of the following four criteria: 1) not intended to acquire, process, or analyze a medical image or a signal from an in vitro diagnostic device or a pattern or signal from a signal acquisition system (section 520(o)(1)(E) of the FD&C Act); 2) intended for the purpose of displaying, analyzing, or printing medical information about a patient or other medical information (such as peer-reviewed clinical studies and clinical practice guidelines) (section 520(o)(1)(E)(i) of the FD&C Act); 3) intended for the purpose of supporting or providing recommendations to a health care professional about prevention, diagnosis, or treatment of a disease or condition (section 520(o)(1)(E)(ii) of the FD&C Act); and 4) intended for the purpose of enabling such health care professional to independently review the basis for such recommendations that such software presents so that it is not the intent that such health care professional rely primarily on any of such recommendations to make a clinical diagnosis or treatment decision regarding an individual patient (section 520(o)(1)(E)(iii) of the FD&C Act).

4 Page 8 of the FDA Guidance.

5 The International Medical Device Regulators Forum (IMDRF) Framework for software as a medical device (SaMD) referenced on page 13 of the FDA Guidance.

6 Page 13 of the FDA Guidance.

7 Page 13 “Software as a Medical Device”: Possible Framework for Risk Categorization and Corresponding Considerations http://www.imdrf.org/docs/imdrf/ final/technical/imdrf-tech-140918-samd-framework-risk-categorization-141013.pdf.

8 Page 13 “Software as a Medical Device”: Possible Framework for Risk Categorization and Corresponding Considerations.

9 Page 23 of the FDA Guidance.

10 Page 23 of the FDA Guidance.

11 Page 24 of the FDA Guidance.

12 Page 8 of the FDA Guidance.

13 Page 17 of the FDA Guidance.

14 The FDA provides several examples in the proposed guidance and it may be helpful for a digital health company to review the full list.

15 You may submit comments and suggestions regarding the FDA draft guidance within 90 days of publication in the Federal Register of the notice announcing the availability of the draft guidance. Submit electronic comments to https://www.regulations.gov. Submit written comments to the Dockets Management Staff (HFA-305), Food and Drug Administration, 5630 Fishers Lane, rm. 1061, Rockville, MD 20852. Identify all comments with the docket number FDA-2017-D-6569.

Qualifying for FDA’s Medical Software Exemptions

By Paul Gadiock

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) continues advancing regulatory policies tailored to the digital health community. In a series of recent guidance documents discussed in this article, the agency has formalized the legislative deregulation of certain medical technologies that aim to transform healthcare.

The 21st Century Cures Act (the “Cures Act”) describes software functions that are excluded from the definition of a medical device. In particular, Section 3060(a) of this legislation, titled “Clarifying Medical Software Regulation,” indicated that the following general categories of medical software functionalities are now outside the scope of FDA device regulation:

- Software Function Intended for Administrative Support of a Healthcare Facility— software function that is intended for administrative support of a healthcare facility, including the processing and maintenance of financial records, claims or billing information, appointment schedules, business analytics, information about patient populations, admissions, practice and inventory management, analysis of historical claims data to predict future utilization or costeffectiveness, determination of health benefit eligibility, population health management, and laboratory workflow.

- Software Function Intended for Maintaining or Encouraging a Healthy Lifestyle—software function that is intended for maintaining or encouraging a healthy lifestyle and is unrelated to the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition.

- Software Function Intended to Serve as Electronic Patient Records—software functions that are intended to transfer, store, convert formats, or display electronic patient records that are the equivalent of a paper medical chart are not devices, if all the following three criteria are met:

- 1) such records were created, stored, transferred, or reviewed by healthcare professionals (HCPs), or by individuals working under supervision of such professionals;

- 2) such records are part of information technology certified under a program of voluntary certification kept or recognized by the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC); and

- 3) such software functions are not intended for interpretation or analysis of patient records, including medical image data, for the purpose of the diagnosis, cure, mitigation, prevention, or treatment of a disease or condition.

- Software Function Intended for Transferring, Storing, Converting Formats, Displaying Data and Results—software that is intended for transferring, storing, converting formats, or displaying clinical laboratory test or other device data and results, findings by a healthcare professional with respect to such data and results, general information about such findings, and general background information about such laboratory test or other device, unless such function is intended to interpret or analyze clinical laboratory test or other device data, results, and findings.

On September 27, 2019, the FDA issued five policy documents that formalize the exemptions provided by the Cures Act: Changes to Existing Medical Software Policies Resulting from Section 3060 of the 21st Century Cures Act; General Wellness: Policy for Low Risk Devices; Off-The-Shelf Software Use in Medical Devices; Medical Device Data Systems, Medical Image Storage Devices, and Medical Image Communications Devices; and Policy for Device Software Functions and Mobile Medical Applications (originally titled “Mobile Medical Applications”). Almost all of these guidances had initially been issued prior to the enactment of the Cures Act. However, once the law was enacted, conforming changes were required in the guidances to reflect the new boundaries of FDA regulation. In fact, some policies in the guidances served as a blueprint for the subsequent medical software legislation, resulting in similarities between the regulatory outcomes of the guidance documents and the Cures Act. Certain updates to the guidance documents, however, represent important distinctions. For example, under the previous iteration of the General Wellness Guidance Document, a subset of medical software was considered by the agency to be under enforcement discretion meaning that the FDA did not intend to enforce the applicable regulatory requirements, but reserved the right to do so in the future. Now, the FDA concludes in the newly-issued General Wellness Guidance Document that the subset is not within the scope of products the FDA has the authority to regulate at all.

Exempted Software Categories

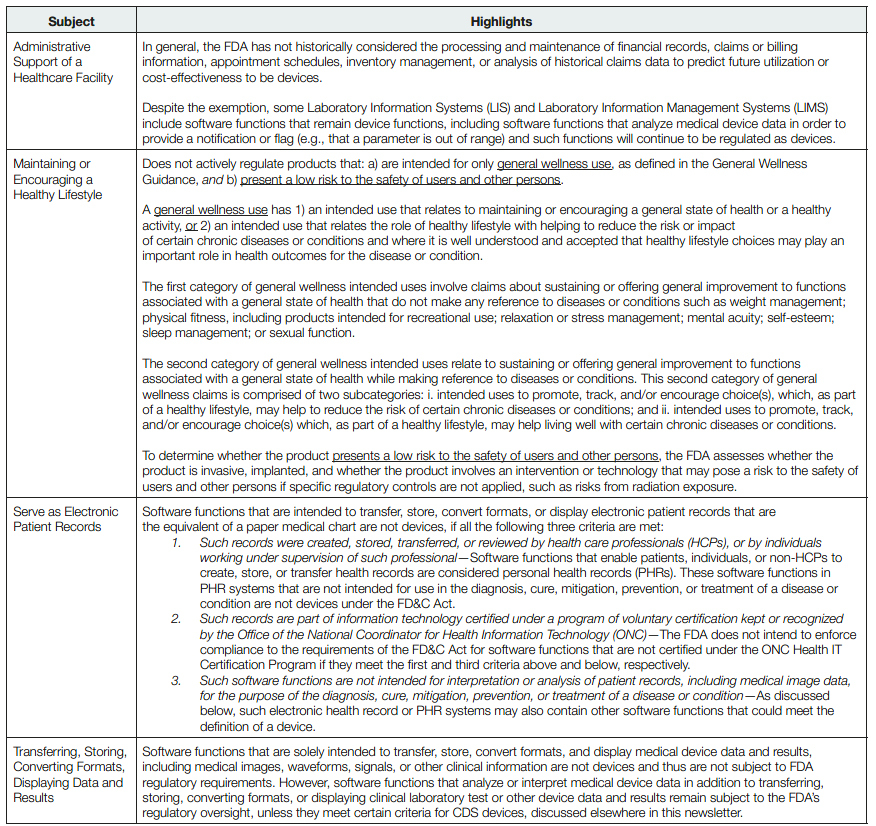

Under the paradigm established by the Cures Act, many manufacturers and investors are recalibrating their products and businesses to fit within the respective statutory exemptions and avoid FDA regulation throughout their products’ lifespan. Others, however, take the position that initially minimizing regulatory oversight facilitates momentum and goodwill that can be leveraged after time to provide novel functionalities that may be subject to FDA oversight, but with a greater upside than their unregulated counterparts. Naturally, this determination is heavily influenced by the goals of the company, the particular functionalities of the software, and the regulatory boundaries enforced by the FDA. To help evaluate the impact of the regulatory categories addressed in the Cures Act, the table below highlights some of the central considerations to qualify for the exemptions.

Conclusion

Readers should keep in mind that the exemptions above are geared toward individual software functionalities, of which there may be multiple in a given platform. The Cures Act provided that, in the case of a product that contains at least one software function that meets the definition of a device and one software function that does not meet that definition, the FDA may not regulate the non-device software function as a device. However, the FDA may still assess the impact of the non-device software function on the device function when assessing the safety and effectiveness of the device function. Therefore, although each software functionality should be evaluated individually, that does not mean it should necessarily be evaluated independently as the relationships between the functionalities may dictate how the product is regulated by the FDA, if at all.

|

This report was edited and published by attorneys from the firm’s corporate, intellectual property, litigation, and regulatory departments, including the following attorneys:

|

Click here for a printable version of the Digital Health Report

This communication is provided as a service to our clients and friends and is for informational purposes only. It is not intended to create an attorney-client relationship or constitute an advertisement, a solicitation, or professional advice as to any particular situation.

Contributors

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Accessibility